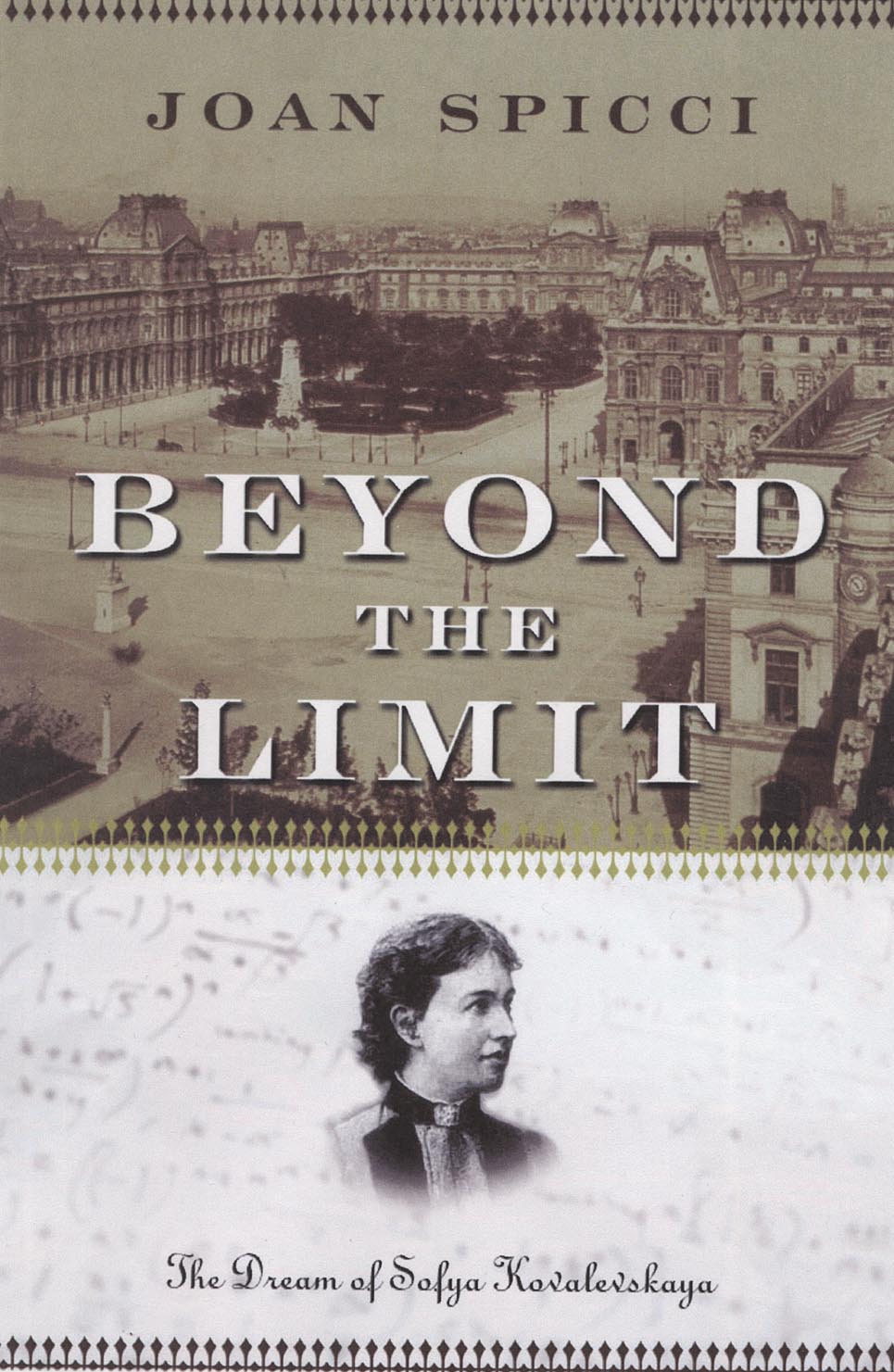

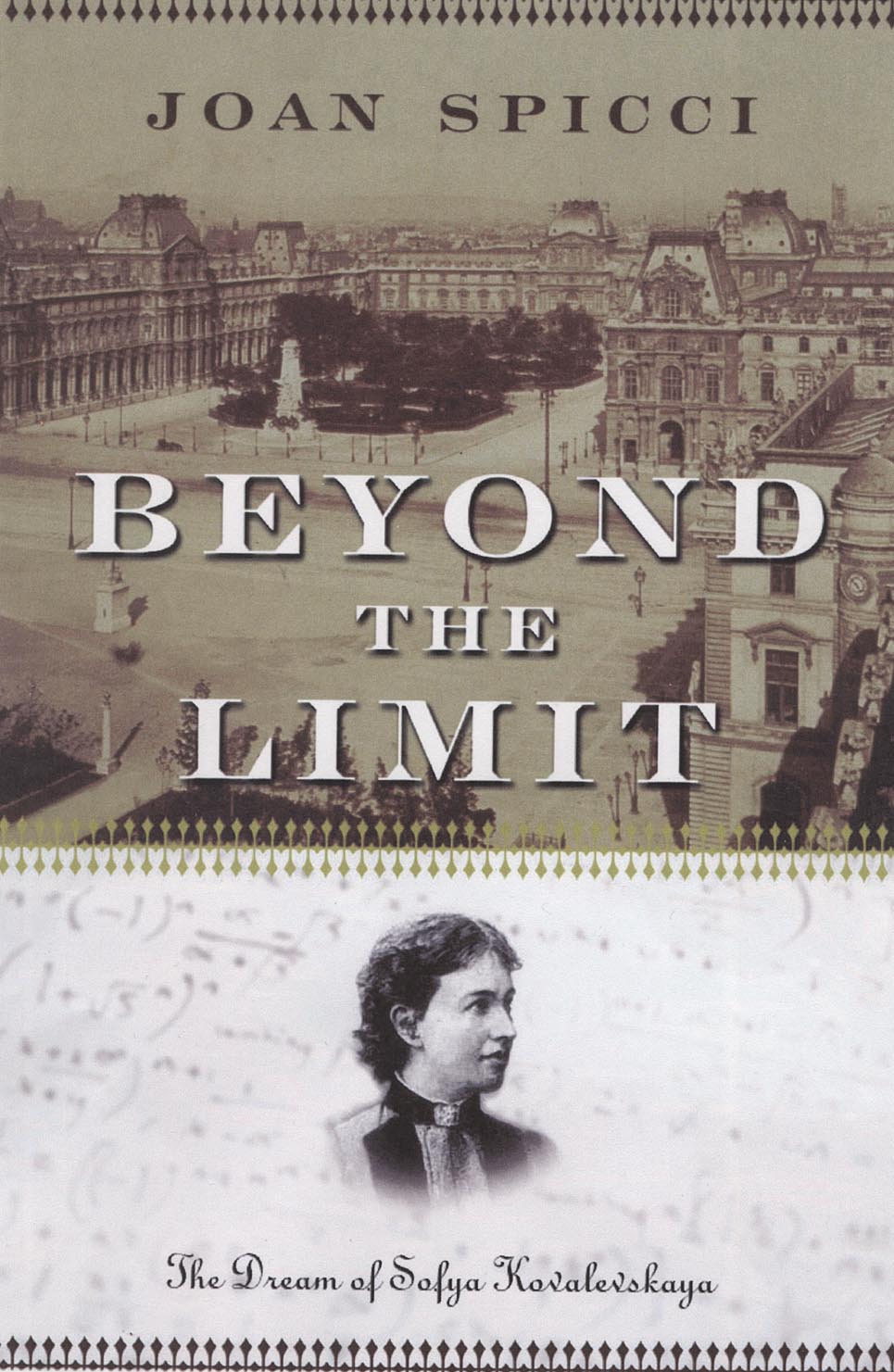

The Dream of Sofya Kovalevskaya

The Dream of Sofya Kovalevskaya

ISBN: 0-765-30233-0

Hardcover/$25.95 US

5 1/2 " x 8 1/4" / 448 pages

Forge Books

Release date: August,

2002xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Purchase BEYOND THE LIMIT at Joan's Bookshop

Excerpts from REVIEWS of BEYOND THE LIMIT ***Brief DESCRIPTION from the book cover

CHAPTER ONE Winter 1865 -- Petersburg, Russia

A real-life Russian mathematician is the unlikely heroine of Joan Spicci's historical novel Beyond the Limit: The Dream of Sofya Kovalevskaya. Based closely on Kovalevskaya's actual experiences, the book follows the young woman through the 1860s and '70s as she fights to get a mathematics doctorate at a time when such an education was unheard of for women. .......... Spicci's engaging story is set against the whirl of St. Petersburg society and the political upheavals of the 1860s.

Joan Spicci creates realistic characters based on historical personages. She writes dialogue that sounds like the things people would be likely to say in a given situation. And she knows how to choose the events that are significant for her characters' development and to narrate them in a way that holds the reader's interest. My advice is to buy the book and read it. I think you'll enjoy it.

NOTICES OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION. January 2004. p39-42.

Who will be interested in reading this book? Any mathematician or scientist with a desire to immerse herself/himself in the vanished world of nineteenth-century European intellectual and cultural life will find Beyond the Limit absorbing.

The book also might be attractive to young women (possibly at the advanced high school level but more probably college age) who like to read biographies of successful women of the past. This is the kind of biography that I read avidly when I was a teenager, and although prior knowledge of Kovalevskaia's history might be helpful, it is certainly not essential for the enjoyment of this charming story.

Full review at http://www.ams.org/notices/200401/rev-annkoblitz.pdf.

Reviewed September 1, 2003. A Sonderbooks' Stand-out of 2003: My Favorite Adult Book of the Year

All at once, this book is a fascinating historical novel, a captivating love story, and an inspiring story of someone triumphing against all odds.... This is a dramatic and suspenseful story, another one I couldn't stand to stop reading even to sleep. Of course, it was extra easy for me to identify with Sofya, since I was once in a doctoral program in Mathematics myself. ... I don't think that you would have to be interested in mathematics to love this book.... When I looked up the book on Amazon, I noticed that every single customer review had given it five stars. So I'm not the only one who liked it!

Additional reader reviews can be found on the Amazon listing of BEYOND THE LIMIT : THE DREAM OF SOFYA KOVALEVSKAYA.

Read an INTERVIEW with the author, Joan Spicci Saberhagen, regarding the creation of BEYOND THE LIMIT at BlogCritic Magazine. By Parker Owens. October 24, 2005.

BEYOND THE LIMIT a novel researched for more than ten years by mathematician and educator Joan Spicci, is the true story of Sofya Kovalevskaya's remarkable personal journey, from the constricted life of a teenage girl in St. Petersburg to the triumph of becoming the first woman to earn a doctorate in mathematics.

For more than one hundred years, Kovalevskaya's struggle has inspired women of all nations to fight for educational opportunities. The full drama and power of her struggle has never been told as it now unfolds in this thoroughly researched novel.

Based on Kovalevskaya's own writings, and many other sources, the story of her early life plays out across a Europe torn by war and political unrest through the turbulent, intellectually challenging 1860s and 1870s. This extraordinary work chronicles the struggles of a brilliant, complex woman on a quest that seems almost impossible to imagine, more than a century later. Friends with some of the intellectual giants of her time, ranging from Dostoevsky to Darwin, she was destined to join their circle.

In the Russia of the 1800s young women are expected to do as their fathers order. After marriage is arranged, they are controlled by their husbands. But Sofya Krukovskaya would have none of this. Born to a family of minor aristocracy and major academic achievement, Sofya learned basic mathematics from private tutors. But only at a university could she realize her full potential. In order to achieve that goal she enters into a marriage of convenience with a young publisher of popular science, Vladimir Kovalevsky.

However, leaving Russia is only the first hurdle. The universities of Western Europe refuse to accept women as serious students of mathematics. Eventually her talents come to the notice of the great mathematician Karl Weierstrass, and under his guidance she at last is able to earn her doctorate.

Sofya is very close to her sister Anya, a talented writer deeply involved with political radicals. In the bloody Paris Commune of 1871, Sofya must forsake her own goals to rescue Anya from ruin, and even death.

Sofya and her husband have a complex, volatile relationship. Loving each other, they're forced by the needs of their careers to endure long separations and other trials. Across Europe, through tragedy and finally triumph, their story is richly told against the backdrop of history.

----------------

Mathematician and educator Joan Spicci's compelling narrative accurately documents Sofya's early life, in BEYOND THE LIMIT: THE DREAM OF SOFYA KOVALEVSKAYA. This fascinating, intimate portrait of Sofya Kovalevskaya confronts issues of equality and feminism that continue to face women who seek careers in the sciences in the twenty-first century.

JOAN SPICCI is a mathematician and educator. She has translated some of Sofya Kovalevskaya's works into English. She lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with her husband, the author Fred Saberhagen.

---------------

The Dream of Sofya Kovalevksaya

by

Joan Spicci

©2002, Joan Spicci

Winter 1865 -- Petersburg, Russia

Dostoevsky in the next room was whispering something in Anyuta's ear, and Anyuta was giggling now. Sofya at the piano, her nerves tight with the strain of trying not to listen to her older sister, could feel the Pathetiqué breaking all to pieces in her fingers. Murmuring prayers and forbidden curses under her breath, Sofya stared at the music and tried to find the magnificent patterns of Beethoven once again.

The piano in her aunts' apartment was an aged and mellow instrument recently tuned in honor of their arrival. For the first time, Sofya had been allowed to accompany Mother and Anyuta to the city for the winter season. Mother insisted that Sofya, now a young woman of fifteen, must be introduced to the culture of the capital, to balls, to the theater, to the young men of her own class. Her tomboy winters spent in the countryside with Father and Fedya, her young brother, must come to an end.

At first Sofya resented the forced change in her routine. Winters at home at Palibino were her time of freedom. Freedom to slide down the banisters, without Mother's lectures on unfeminine behavior. Freedom to listen to Father's conversations with his male friends on politics, science, and mathematics. Freedom to explore the universe contained in Father's library, a universe where she traveled alone, fueled by curiosity, on journeys forbidden under Mother's watchful eyes. The winters had been lonely without her older sister, but that loneliness had been bearable.

As far back as Sofya could remember, she had admired and envied her beautiful, spirited, older sister. And Anyuta had treated her as a tag-along annoyance. Then, once Mother had decided that Sofya was old enough to come to Petersburg, Anyuta's attitude suddenly changed. She began to talk to Sofya as a friend, almost as an equal. Sofya reveled in the change, even though she suspected Anyuta was mainly interested in securing a loyal ally in the city. Anyuta wanted to be a 'new' woman and Petersburg was the center of the 'new' women's world.

For Sofya, the most wonderful of all the delights of the big city was not the company of new women, but the older man who was now alone with her sister in the adjoining room. To be near this man would be to know freedom without loneliness. With a man like him, in a place like Petersburg, her life could be a Beethoven sonata.

For the first time, Sofya was glad Mother forced her to practice the piano. There seemed a chance that her playing would please the great Dostoevsky. The key for the lower C sounded a full, round pleasing tone. The Middle B-flat responded to her slightest pressure. The Petersburg piano came alive even under Sofya's straining fingers.

At the moment the two sisters and their visitor had the apartment to themselves, except for a couple of servants who were taking care to be unobtrusive. Sofya's two Aunties, Mother's sisters, were well past their youth. Aunt Alexandria was a widow, and Aunt Sofya a spinster. They owned this apartment, and for that matter the entire building, occupying a full block on Petersburg's Vasilievsky Island.

A special sale on party dress material had been announced in the morning paper, and two hours ago the Aunties had gone out shopping, taking Mother with them. Their destination was Passage, the mammoth cloth warehouse and shopping arcade on Nevsky Prospekt. No sooner had the three women departed than daring Anyuta had sent a servant girl with a message for Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky.

"Anyuta, Father forbade you to see Dostoevsky without Mother being present," Sofya scolded as soon as the servant was gone. "Father says Dostoevsky's an unsuitable companion."

Anyuta flung herself into a chair. Sofya watched as a cat-like smile spread from eyes to her lips. ""Father says, Father says!"" Anyuta lowered her voice to imitate Father's deep tones. "Dostoevsky is in poor health. Dostoevsky is a widower. Dostoevsky struggles to support his dead wife's grown, good-for-nothing son. Dostoevsky is in the filthy business of journalism, and he's not making any money. And on top of that, he was a convict. Altogether, an unsuitable companion!"

Anyuta again changed her voice, this time to imitate Mother whispering. "I have heard that Dostoevsky was seen in all the gambling dens in Europe with the daughter of a wealthy merchant."

Sofya laughed at Anyuta's accurate impersonations. She admired her sister greatly for never being intimidated by Mother or Father.

Anyuta continued now in her own voice, "He was seen in the spa at Baden-Baden with Polina Prokofevna Suslova. Everyone knows about that." Anyuta's eyes twinkled. "He's the most interesting man I've ever known. And, he's published my short story in his journal. I will meet with him!"

"Remember the last time Dostoevsky was here . . ."

The smile left Anyuta's pretty face. "Yes, my dear little sister, I remember." Her voice turned angry. "I remember how Mama flustered him with her silly questions and senseless talk of the weather. You don't talk to a sensitive man like Dostoevsky that way. And the Aunties! They kept making excuses to come into the room just to look at the man. He must have felt like a creature in the zoological gardens, being gawked at by Sunday visitors. Now I have a chance for friendship with this extraordinary man, and I won't let it be destroyed by those foolish women. And I don't want him to think my whole family is scatterbrained."

Anyuta's eyes were shining mischievously. She stood up and walked nervously about the room. She picked up a trifle of pottery from a table, traced its glazed surface with her fingers, then replaced it. "I must talk with him where we can be free of Mother and the Aunties."

"Mother will send you back to Palibino, if she hears about it."

Anyuta shook her head and spoke slowly, as if to a child. "Sofya, Mother will not send me back to Palibino. She wants me to stay in Petersburg and find a husband. I'm being displayed, Sofya. The custom is very old-fashioned and most disgusting."

Anyuta smoothed her dress as she spoke. Then she daringly unbuttoned the top button on the bodice.

Sofya looked at her with envy. Anyuta was twenty-two. Her thick blond hair and flawless fair complexion made her a classic beauty. Her fine features reminded Sofya of a porcelain doll. Today the older sister was wearing a blue poplin dress trimmed in blue silk. A narrow blue belt with a delicate silver clasp accented her tiny waist. Anyuta refused to wear a bustle. Progressive young women often protested against such decorations, and anyway, on Anyuta's tall, slim figure the soft folds of the dress in a natural shape were more attractive.

Sofya glanced down at her own knee length dress, a dark blue cotton bibbed jumper with a blue striped blouse. The dark cotton stockings she wore no longer clung neatly to her legs, but sagged loosely at the ankles and calves. The color of her dress did not flatter her dark complexion and unruly, wavy dark hair. She was sure the outfit made her look short and chubby. Unbuttoning the top button of her blouse would have been useless. Sofya was painfully aware that she had nothing to show with a decolletage. Had she known Dostoevsky was coming, she would never have worn this childish jumper. Now it was too late to change.

Anyuta smoothed her hair with her hand and turned around slowly. "Do you see any strings or lint?"

"You look very elegant," Sofya assured her.

Satisfied, Anyuta sat down on the divan and began to flip through the pages of the weekly literary journal. Sofya sat at the opposite end of the divan with her legs tucked under her.

Anyuta spoke defiantly, but quietly, as if she were bolstering her own courage. "I want to see Fedor Mikhailovich. I will see him, away from Mother's prying eyes." Anyuta flipped the pages of the magazine. "Mother and Father's rules can be opposed." She looked at Sofya. "You've opposed them. You have courage and fortitude. By wit and clever persuasion you disposed of that awful governess Miss Smith at least a year before Mother and Father intended. But you haven't yet developed cunning. Your attacks are too direct. Watch me and learn, little sister."

Sofya felt admiration, mixing with apprehension that in this case Anyuta might have miscalculated the power of parental authority. On several occasions, she had watched Anyuta's plans, strong on initiative and weak on strategy, go awry. Still, being a partner to a forbidden enterprise was exciting. Anyuta trusted her as an accomplice in this bid for independence and freedom.

Within half an hour, marked by the slow-ticking clock in the next room, someone knocked at the door.

Before answering, Anyuta looked around the room nervously. Then she waved her hand towards the piano. "Sofya, play something for us. Set a proper, cultured mood. Something by Beethoven. Dostoevsky loves Beethoven."

Sofya hurried to the piano, anxious to please their guest.

Sofya heard the door open, and then the warmth of her idol's voice. She did not even turn to look as Anyuta showed Dostoevsky into the adjoining room.

Soon, laughter came from that next room. Sofya paused in her playing and stared at the silent keys, her fingers idle for the moment. She had completed the first movement of the sonata. Her fingers ached. She waited for applause, some sign of appreciation. None came.

What could be occupying her audience? Might it be only in her imagination that her sister and the famous writer were sitting close together in there? Close enough to exchange whispers inaudible a room away?

The white door to the next room stood open and now from beyond it there was only silence. Sofya arose and went quietly to the door. Neither the kerosene lamps nor the candles had been lighted in the small sitting room beyond, though only a pale glow of daylight came in through the frosty windows. The dark red wallpaper with its maroon vertical stripes, the matching velvet of the divan, the darkly painted floor all contributed to the dimness.

Anyuta was seated on the divan, her left profile turned in her sister's direction. Her face was most flatteringly silhouetted. The afternoon's fading light was at her back.

Dostoevsky, seated an arm's-length away, leaned towards her. His hand, with fingers spread, pressed on the cushion that separated them.

Anyuta looked down at Dostoevsky's hand. She slowly fingered the velvet-edged cushion that separated them. Her lips were turned up slightly in a half smile. With difficulty Sofya controlled a wave of jealousy. She had seen Anyuta use this exact expression and stance when flirting with other suitors.

Dostoevsky's left hand reached out and enclosed Anyuta's.

The pale light was focused on Fedor Mikhailovich, who looked sickly and tired today, worse then when Sofya had seen him last, months ago. His brown tweed suit coat hung from his shoulders as if it were a size too large. The black trousers draped too loosely over boots that did not match his jacket. His linen shirt was clean, but too shiny at cuffs and collar, much too worn for proper fashion. His whole appearance was disheveled, clothes wrinkled as if he'd slept in them. His unkempt reddish hair and beard were turning gray by the month.

Dostoevsky was speaking. "Anyuta, I read your sensitive nature in your stories, and in the letters we have exchanged." He stuttered for a moment and went on, "I had hoped your letters would be filled with warmth. Letters of a Tatyana to an Onegin. I dreamed. . ."

Anyuta looked at him with a full smile. His face grew redder as he added: "Of course, letters like that can only have been written by a Pushkin."

Sofya thought he was talking too quickly, almost as if he were afraid of what might happen if he stopped. When he paused for Anyuta's reply, he bit his lower lip. His fingers nervously pulled at the hairs of his sparse beard.

Anyuta answered in a laughing tone, that sounded to Sofya like an imitation of innocence. "I too love Pushkin, but one thing puzzles me. Sometimes he writes with such admiration of his heroine's feet. I am at a loss. Can it be that a woman's feet are so very attractive to a man?"

Now Anyuta stared at her own feet, crossing and uncrossing them rhythmically.

Anyuta was wearing her blue velvet embroidered house shoes, without any stockings. A trace of bare ankle was visible even to Sofya.

Dostoevsky's gaze became fixed on the shifting feet, while he continued to talk more nervously and excitedly than before. "I am sure that the great master knew very well the nature of a man in love."

Dostoevsky's face was now very red.

"We will speak of something else." Anyuta slowly pulled her hand away from Dostoevsky's. She sat more rigidly, folded her hands in her lap. The action appeared to make Dostoevsky's discomfort even greater. There was silence. Then at last Anyuta continued, "Tell me about your business. The journal is doing well?"

In a moment Fedor Mikhailovich, much more at ease, was telling Anyuta of his efforts to organize the next issue of his journal, Epoch.

Anyuta appeared to listen attentively to her companion's outpouring of difficulties, now and then interrupting with comforting or encouraging words.

Sofya, stung by the fact that her efforts at the piano had been ignored, was standing boldly in the doorway, hands on her hips. Surely the couple must be aware of her presence.

But they seemed to have eyes only for each other. "Anya Vasilievna," Dostoevsky said, breaking a pause in the conversation. "I'm very glad you asked me to come. I was afraid that you would never want to see me again. After our last meeting, I was sure you thought me a raving madman, unfit for a proper woman's society."

Still he had not turned his gaze toward the doorway. Sofya wondered if he really did not see her.

"Nothing of the kind, Fedor Mikhailovich," Anyuta assured him sweetly.

"Oh, but you must have! I couldn't, I really couldn't, speak sense in front of your Mother and your aunts." Nervously his hands played with the edge of his coat, then passed over his knees in a rubbing motion. "I know this happens to me. I become tongue-tied and stupid whenever I'm with people who make me uncomfortable. In my discomfort I begin to talk about things that are totally inappropriate to the situation. I can't stop myself. I talk and talk. Finally, I feel the people around me are totally disconcerted and want only for me to leave. That's what happened that night with your family." He paused and folded his hands together almost as in prayer. "Please forgive me."

His speech completely wiped out Sofya's jealousy. She wanted to shout her forgiveness, her understanding, to take his hands and hold them to her cheek. She would confess that she too had felt the sting of social ineptitude. But he wouldn't even look at her. She remained at the doorway, hands now limp at her sides, and watched.

Slowly Anyuta lifted her chin. It seemed to her sister that she was drawing out her actions like the heroine in some melodramatic play. Didn't Dostoevsky see how she was playing with his emotions? Of course Anyuta could know nothing of the discomfort Dostoevsky had expressed. Sofya had never, ever, seen her older sister uncomfortable in any social situation.

At last Anyuta glanced toward the doorway, briefly acknowledging Sofya's presence. Blushing with embarrassment at the possibility of being thought an eavesdropper, Sofya edged back a little into the room where the piano waited.

Meanwhile their visitor, looking as awkward as a raw youth, still had not glanced in Sofya's direction. He grasped Anyuta's hand again, and for a moment Sofya wondered if he was going to kiss it, not formally as he had done on entering the apartment, but with an unrestrained passion. Sofya's eyes widened expectantly.

Anyuta stood up quickly. Dostoevsky was still grasping her hand and staring at her, his eyes blazing. He seemed on the brink of some great declaration.

"Fedor Mikhailovich, we are not alone!" Anyuta reprimanded him. "My sister is present."

Sofya felt the blood rushing to her cheeks. She wanted to hide, or perhaps even to cry. Would the great man now consider her an eavesdropper?

Dostoevsky's eyes turned toward her, at first blankly, as if he had forgotten who she was. Then they began to twinkle in a gentle, childlike way. Sofya sensed that again they shared a common feeling.

He stood up, brought his heels together and bowed slightly in her direction. "I thank you for the lovely piano music." The words sounded perfectly sincere. There was no mockery, no condescending to her youth. Again Sofya felt herself blushing, this time with pleasure.

Anyuta came to stand behind her sister, placing her hands on Sofya's shoulders. "Fedor Mikhailovich, on your last visit you encountered some of the older women of our clan. Their frivolous talk made you uneasy. I will demonstrate to you that the younger women of this clan are not foolish. " Anyuta's voice carried a hint of playful mockery. "For myself, I have already offered you my work as an author."

"But I didn't mean . . . " Dostoevsky started, but Anyuta interrupted.

"I am not unique. I am not an oddity. Others of my sex and generation are engaged in serious endeavors. I present to you another woman," she laughed at her own theatrics, "well, a very young woman, of the clan Korvin-Krukovskaya. Fedor Mikhailovich, my young sister writes verses!" Anyuta's eyes were glowing, her face flushed, she was beautiful. "Let me get the poems for you." Then the older sister, her skirts swirling, disappeared from the room.

Sofya, in agony as to whether she should protest or not, looked to Fedor Mikhailovich. His eyes were not on her. The man of experience was staring after Anya; it was a hungry, almost hopeless look.

Will any man ever look at me like that? Let alone a noble, wise, sensitive man like this one . . .

Fedor Mikhailovich continued to look right past her, through the doorway where beautiful Anyuta had disappeared.

Sofya felt herself growing very warm all over. She had written the verses only to amuse herself while playing in the halls at Palibino. She was proud of them, but she knew they were only a beginner's attempt.

Anyuta returned, walking calmly, unhurried now. Silently she handed Sofya's notebook to the visitor. Anyuta and Dostoevsky's eyes met and lingered.

Anyuta moved about the room, lighting lamps. The increased light and the smell of kerosene drove the last wisps of magical romance from the room.

Dostoevsky took out a pair of steel-rimmed reading glasses and put them on. Then, slowly turning pages, he read out loud the titles of her poems.

"'The Bedouin's Address to His Horse'--'The Sensations of the Fisherman as He Dives for Pearls'--'The Fountain Jet.' Well, let us see what we have here." Then, moving nearer a lamp where the light was stronger, he read quickly and silently to himself.

For a moment or two after he had finished reading Fedor Mikhailovich was still. Then he raised his eyes to Sofya -- it was almost as if he were looking at her for the first time. "But this is very, very good. You show great promise."

Sofya had to steel herself against a wave of faintness. What ought she to say? "Thank you." In her own ears her voice sounded foolish.

"Some day, you too may be a published writer like your sister. But you must work at it very hard. Just as your sister will." And Dostoevsky's gaze returned lovingly -- yes, that was the word -- to Anyuta.

Anyuta had seated herself on the divan again. Noticing Sofya's deep blush, Anyuta mischievously chose to prolong her sister's discomfort. "Sofya's also very good at the sciences. Her tutor is very much impressed with her quickness at mathematics, though Mother thinks Sofya's already absorbed quite enough geometry and so on for a woman."

With a frown and a shake of the head, Fedor Mikhailovich demonstrated his scorn for such an illiberal attitude. Doubtless, thought Sofya, his reaction would have been stronger had it not been directed at Mother.

With a playful laugh Anyuta continued: "The two of us share a room while we're staying here in Petersburg. And late at night, when Sofya thinks no one is looking, she brings out a secret book and reads it by the light of the icon lamp. You'll never guess what she's reading."

Sofya was mortified. This time her sister had really gone too far. Sofya had been flattered to support a point in sister's argument. Now Anyuta, sensing she was in complete control of the situation, was letting her playful nature take over. Sofya knew and dreaded that teasing tone in Anyuta's voice. "Please! Anya!"

Anyuta was not to be put off. "Guess, Fedor!"

Fedor Mikhailovich looked uncomfortable. But he was under Anyuta's spell, he could not refuse. "A romance by George Sand?"

"No! Guess again!"

He looked surprised at the failure of that first guess. Sofya could see him thinking: But what else is a young girl likely to want to read?

"Guess again!" Anyuta insisted in a playful way.

Taking up Anyuta's teasing tone, he answered "How about Herzen's The Bell--or one of the other forbidden progressive journals her older sister hides away?"

"Anya, you promised not to tell!" Sofya tried again to stop her sister.

Anyuta ignored Sofya's entreaty. "No! You'll never guess it. She's reading an algebra book she's sneaked from our Father's library!"

An angry pounding was beginning in Sofya's head. She had been betrayed. In a moment of confidence, Sofya had tried to explain to her sister her fascination with algebra. Just as words and images of poetry opened a room in her soul, so too the symbols and logic of mathematics opened a similar room. Anyuta's complete lack of understanding and her cruel laughter left Sofya with the feeling that her attraction to mathematics was unnatural. And now Anyuta was laughing again.

After a moment of silence infinitely painful to Sofya, Fedor Mikhailovich responded, "Such talent," his eyes moved slowly from her face to her feet, then back to her face, "and such a pretty girl."

Sofya was looking straight into his eyes, and for a moment there was a distance in his look, an utter lack of comprehension, that chilled her heart. Even he, who was educated as an engineer, did not understand her feelings for mathematics.

Then he must have seen her pain for his eyes softened, he rallied. "You know that you have extraordinary gypsy eyes?" he said just above a whisper.

Was it possible that he really thought her pretty? Her pain vanished. Sofya felt her cheeks warming to a blush. She longed to say something clever, something that would keep his eyes on her.

He must have interpreted her silence as a conclusion. He turned towards Anyuta who was seated on the divan. Sofya watched as Anyuta captured his complete attentions. Sofya remained in the room, her presence unrecognized. Once more she watched Fedor Mikhailovich with silent admiration.

"Your demonstration of talented young people reminds me of an incident that occurred on my way here today." He was talking almost to himself as much as to Anyuta. "What a varied group you young people are."

"Whatever are you referring to?" Anyuta asked with a joking tone in her voice, a little blush coming to her cheeks.

"As I was rushing here from my office, I saw a young boy, a newspaper seller, about the same age as your sister. Poor fellow had no overcoat and was clutching his light jacket closely to his body. The boy possessed a natural spirit of friendliness mixed with subservience so common in our lower classes. The young salesman called out a synopsis of the day's stories.

"A brassy young man dressed in the smart uniform of the Tsar's Corps des Pages, a young man no older than the our paper seller, complained loudly that the paper was, indeed, yesterday's paper and not the latest morning issue. Our paper seller was thrown into confusion. Clearly this seller of papers could not read.

"The Page in his sparkling uniform was laughing.

"The paper seller rushed off in despair, eyes so clouded with tears that he collided with me. Our eyes met. I saw the look of the humiliated, the trapped. The eyes of a prisoner. A look I have seen all too often."

For a moment the room was still.

Sofya and Anyuta were waiting for Dostoevsky's next words. None came.

"Prison must have been unbearable for you." Anyuta was trying to bring her visitor out of his trance like state.

"Had it not been for the kindness of one aristocratic woman, a Decembrist's wife, I would have lost my senses." Dostoevsky was thoughtful, then continued, "When I stepped from the train and looked around at the vast bleak horizon of the Siberian landscape, when my mind raced forward to the years I would have to spend in desolation, this woman came up to me. With a smile, she handed me a book, the Bible."

"She said nothing to you?" Anyuta asked.

"Only that she would pray for me, as she did for all prisoners," Dostoevsky continued. "During the first year of my imprisonment, I was allowed no books, other than that Bible. I would have lost my mind had I not had that book. It will always be my most cherished possession. A reminder that I was a prisoner, that I was saved from madness by a stranger's kindness. And that without the law and hope offered in that Book, all is lost."

Sofya's eyes were wide with fascination as she asked, "Did you meet any murderers?"

"The politicals, like myself, were in the same dormitory with the civil criminals. Yes, I came to know many murderers, rapists, thieves, arsonists. I came to know how they think and what they feel. Prison is so . . ." He broke off suddenly. "But I had not meant to torment two lovely young ladies with such horrors. The Tsar's page was a prisoner of his training and class, the paper boy a prisoner of his illiteracy. And here in this very privileged house I find two more young people who have had in their eyes, from time to time this afternoon, the look of prisoners. I believe I have guessed what caused this look in each of you."

"You certainly must tell us what you have guessed about us," Anyuta said, with a slight tease in her voice. Only Sofya recognized that there was also dread in her sister's voice.

Sofya silently prayed that Dostoevsky would not go on with his revelation. She felt a chill of fear for her sister and for herself. The man had the power to look into souls.

Dostoevsky looked at Anyuta and then briefly at Sofya. "My dear young ladies, these truths must be discovered, not uncovered."

"Now you are teasing us," Anyuta laughed.

Conversation was interrupted by sounds in the hall. A servant's voice, a door opening. Moments later, Mother came rushing into the room, still wearing her sable coat and hat. Unruly packages threatened to escape from her arms. She gasped and came to a halt as she took in the scene. Sofya could see shock, disapproval, and even a little fear written on her face: Good God, HE's come. And there was no proper chaperone! Dear God, don't let Vasily Vasilievich find out!

Taking advantage of the need to exchange a few words with the servants who came to help with her packages and outdoor clothing, she turned her back to the girls and their visitor. When she faced them she was calm.

Elizaveta Fedorovna Korvin-Krukovskaya was impeccably dressed, as always. She was still very attractive at forty-five years of age, and aware of her attractiveness. On entering the sitting-room she had been in a delightful mood. She loved Petersburg, the shopping, the social life . . . But in the next moment, upon encountering her unexpected visitor, she had become perplexed and indecisive, an attitude her daughters had seen many times. Sofya had long ago decided that Mother was more alarmed by the prospect of her husband scolding her, than she was by Anyuta's sometimes indiscreet behavior.

Anyuta put her arm around mother's waist. "Isn't it wonderful? Fedor Mikhailovich was in the neighborhood and impulsively decided to drop in to see us. We've been having the most enlightening discussion." Mother looked at Anyuta's smiling face, then at Sofya. Sofya did not contradict her sister. Sofya quickly glanced at the visitor to see if he would give them away. But he was looking at Anyuta. His eyes were glowing and he seemed to be suppressing a laugh.

Surrounded by smiling faces and Anyuta's warm hugs, Mother's anger was soon defused.

Mother greeted Fedor Mikhailovich quite civilly, and apologized for not being at home when he had called. Bowing slightly, he returned the greeting.

Elizaveta Fedorovna motioned them all back into the sitting room, where she ordered the servant to bring hot tea and sweets. Mother was soon steering the conversation. Sofya watched, not completely free of contempt, as Mother performed the part of the proper social hostess.

"Is your journal doing well, Fedor Mikhailovich?" Mother asked in an innocent voice, as she poured the tea.

Sofya and Anyuta exchanged worried glances. This could be a point of friction.

"Financially, the journal is barely surviving," Dostoevsky commented. "But money and I have never had a good relationship. On the other side, the stories and comments in the journal are worth the reading. A woman of your sensitivities and love for Petersburg and Russia could only approve of our discussions of social issues. In this month's issue I have included my story, The Crocodile. The story is written in a humorous and fantastic style."

"Fedor Mikhailovich, I do not concern myself with politics or social commentaries or fantasy, however amusingly presented. I am interested in charity work and the arts, especially music."

Sofya heard Anyuta gasp with horror at Mother's response. But Dostoevsky had evidently decided that on this occasion Mother's views were better left unchallenged. He countered them with a compliment. "Your daughter, Sofya, has inherited your musical abilities. She has been most pleasantly displaying her skill for us."

Mother was flattered. "Sofya has a natural talent for the piano, but I'm afraid she doesn't practice as she should."

Sofya blushed at the reprimand. She watched Dostoevsky's face for his reaction. Did he think less of her because of this? She thought she saw him give a quick wink of understanding and reassurance in her direction.

"Sofya has her mind on other interests. Interests she will certainly need to develop." Dostoevsky was soothing. He continued, "All arts must be developed. I strongly urge you to encourage your daughter Anya in the development of her literary talents. She has shown quite a flare."

"My daughter's literary efforts must remain only a hobby for her."

"Mother!" Anyuta burst in. Her face was red with anger.

"The decision to develop their talents is theirs," Dostoevsky paused, "and yours and your husband's. They are also quite lovely ladies. Another quality they have inherited from their mother."

That answer was to Mother's liking. Anyuta was also soothed, although Sofya suspected that Anyuta and Mother would exchange some unpleasant words when the visitor was gone.

An hour later, they were all accompanying Fedor Mikhailovich to the door. He had bowed to Anyuta and Sofya, his eyes lingering rather longer on Anyuta.

Mother offered her hand to the visitor. "Fedor Mikhailovich, I hope you will visit us again soon." Sofya and Anyuta looked on in amazement.

Dostoevsky took her hand and kissed it politely. "The company of cultured women is always delightful." He arranged a woolen scarf around his neck, then pulled his beard out over the cloth. Then he tugged a woolen cap, whose color did not match the scarf, low over the crown of his balding head.

Mother hesitated for a moment as she observed with puzzlement, tempered with warmth, the man's eccentric appearance. Warmth and gentle teasing came into her voice, "Dostoevsky, you are a most brilliant and interesting man. But you really must find a woman to see to your wardrobe!"

Dostoevsky's eyes twinkled. He was not at all offended. "I intend to do that, madame." He bowed again to each of the ladies, his eyes again lingering on Anyuta.

The door closed. Dostoevsky was gone.

Elizaveta Fedorovna turned to her daughters. The smile disappeared from her face. She motioned Anyuta and Sofya back into the living room.

"Well, girls," she began. She was struggling to make her words sound firm and authoritarian. "You allowed yourselves to be put in a rather compromising position this afternoon by entertaining a male caller when there was no suitable chaperone."

"Mother, there was nothing else to do," Anyuta pleaded. "We only wanted to maintain the gracious reputation of our family." Her tone suggested that a sob might be imminent.

Mother paced the room nervously, apparently struggling to maintain an attitude of indignation and parental outrage.

Sofya knew that Anyuta could easily defuse her mother's resolve by forcing an emotional scene complete with sobs, tears and accusations of not being understood or loved. Sofya and Anyuta exchanged looks. Sofya saw that this time, Anyuta had decided not to create such a scene.

"We are guests in your aunts' house. You are to respect the proprieties of the Schubert home. Furthermore, if even a hint of this indiscretion were to reach your father at Palibino, he would order us all back to the country."

Sofya and Anyuta submitted silently to the scolding, aware that Mother's admonitions were largely a result of her own dread of returning to Father's watchful eye and to the loneliness of the country.

After that meeting, Dostoevsky was frequently a guest in the apartment.

On one such evening Anyuta, Sofya, and Mother sat and listened in wonder as Dostoevsky related a scene from a book he was planning.

Mother's eyes were shining and her skin had just a faint flush. With skepticism, Sofya acknowledged the impressions of her senses. She saw a certain subtle flirtation in Mother's attitude toward the visitor.

The observation forced her to think about certain facts she knew already. Dostoevsky was forty-four years old. One year younger than Mother! Twice as old as Anyuta! Almost three times older than herself! These were mathematically true relationships. Of course it was possible to argue that this was only a numerical result, that had no meaning without a physical interpretation. Just as the negative roots of quadratic equations sometimes had to be disregarded, so this mathematical result must be somehow irrelevant to the practical problem.

"Sofya," Mother's voice was calling, "Whatever are you thinking of? I've asked you three times to pass the sugar."

"Sorry, Mama." Sofya passed the silver container, meanwhile silently scolding herself. How could she have let herself be so absorbed in calculations when He was here?

Fedor Mikhailovich's gentle smile at her seemed to say that he understood how much of a temptation one's own thoughts could be.

Then, turning his gaze from Sofya to Mother and then to Anyuta, he continued to relate a scene that he hoped to use in some future book. "The landowner in my story, up to the time of this scene, has shown a fatherly concern for the ten-year-old daughter of his cook. The girl is quite lovely and shows talent as a singer. The landowner has allowed the girl to sit in on the reading lessons given by his son's tutor."

The story teller sat back in his chair, and his gaze went far away. "One evening this wealthy landowner, after a night of drunkenness and debauchery, returns home and instead of going to his room, decides to go down to the kitchen quarters. There the ten-year-old is asleep near the fireplace. The old man's eyes are glowing, he is excessively warm, from drink, from the heat of the fire. A forbidden thought comes to his mind. A thought so heinous that at first he is repulsed. But the thought keeps returning. There is no one else in the room but the girl. And, despite all the pleas of his conscience, he is drawn to the evil deed. He is the master of this house. She is his property. So go the arguments of his crippled mind. And then, this landowner, this man who believes he is the master, the only law on his property, decides to break the law of God. To take advantage of . . ."

"Fedor Mikhailovich, please! Not in front of my daughters!" Elizaveta Fedorovna, whose dismay had been growing, at last interrupted.

With a start, Dostoevsky rejoined his dinner companions. For a moment he seemed not to know where he was. Stuttering an apology, he blushed, and ran a hand nervously through his thinning hair.

His reaction touched Mother, who redirected the conversation. "Speaking of young children, there will be a benefit performance for the city orphanage this weekend. I have an extra ticket, perhaps you would attend, Fedor Mikhailovich." All trace of anger had left Mother's voice.

He accepted the invitation. Sofya listened with tender admiration as Dostoevsky spoke of his visits to the city's unfortunate orphans.

In her secret daydreams, Sofya loved to pretend that she had been with Fedor Mikhailovich in exile in Siberia. In the great self-sacrificing tradition of the wives of the Decembrists, the revolutionaries of 1825, she had followed Fedor into exile. The wretched Siberian natives honored her as an angel of mercy. Her days were spent in doctoring and teaching. She pictured herself working beside Fedor, suffering with him for some great though vaguely defined cause, having much to do with honor and loyalty to friends. He was a man who would never betray his friends.

Sofya and Anyuta were doted on by their spinster Aunties. Excursions to one of Petersburg's museums, libraries, or schools of higher learning were their joy. Frequently Aunt Sofya reminded the girls that their maternal grandfather and great-grandfather had been respected scientists, remembered for their respective contributions to astronomy and geology. They had been good men, and they had stayed away from politics. Aunt Alexandria's stories were different. She had been a teenager during the Napoleonic invasion, and just a young bride at the time of the Decembrist revolt. One of her friends, the wife of one of those ill-fated officers, had died in Siberia.

When the sisters were alone, Sofya confessed that she loved Aunt Alexandria's stories of the old days.

Anyuta groaned, "I don't want to hear history, I want to live it! I want to shape the future world." Anyuta continued in the manner of an instructor, "Have you noticed that when Mother and Aunt Sofya are together they speak in hushed whispers about a handsome military widower or a shy middle-aged professor. In a word, Mother and Aunt Sofya behave like foolish schoolgirls. Thank goodness you and I have better things to talk about than men."

Sofya hesitantly asked, "Do you talk about men with your women friends when I'm not around?"

"Not very often. I wouldn't at all if I could meet some interesting people of my own age. Unfortunately, almost everyone we know is the son or daughter of one of Mother and Father's friends." Anyuta smiled in a way that meant she had a secret. "Still, little sister, some of these young people are beginning to think critically and to whisper their discontent."

"You do more than whisper your discontent, Anyuta." Sofya noted with admiration, "You do manage to make friends outside of Mother and Father's circle. At Palibino you managed a friendship with Semevsky, and then with Filippovich. They were both modern men."

Anyuta raised her chin, and in her sister's eyes took on something of the expression of a general reviewing conquests. "Yes, on a few occasions I have been able to break the parental guard." After a momentary hesitation she added, "Still, Semevsky was sent packing by Father in no uncertain manner. And poor Alexsei Filippovich, his own father disowned him and forced him out of our district!"

"Aleksei pronounced his 'o's' very strongly." Sofya recalled, imitating the country accent precisely, making her sister laugh. "He sounds just like a priest."

"Aleksei acquired that accent from his father, and his training in the seminary just reinforced old habits. He can't seem to escape that part of his background, although his thoughts are freed." Anyuta sighed. "He wasn't at all polished, but he had a wonderful mind. He introduced me to Herzen's weekly newspaper, The Bell." Anyuta became less defensive. "Anyway, who cares if he spoke with an accent." She laughed. "And who cares if his fingernails were always disgustingly dirty."

"No reason to care, since you're not going to marry him," Sofya observed. "We'll never see either of them again at Palibino."

"Small loss. But neither Father nor Mother nor Aunties nor any other force is going to separate me from Dostoevsky.".

The visit to Petersburg would last only a few months. The three Kovin-Krukovskaya ladies would have to return to Palibino before the April thaw made the country roads impassible. The Schuberts planned a large party in honor of their winter guests, and Elizaveta Fedorovna was given full rein in ordering all the arrangements exactly as she liked.

Elizaveta Fedorovna invited some military friends and comrades of her husband, some of Grandfather Schubert's old friends from the university, some distant relatives, and a few old friends from Elizaveta's maiden days. Anyuta suggested a few names from among the sons and daughters of Mother's friends -- and calmly added the name of Fedor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. Mother made no objections.

As the time drew near, Elizaveta worried about the success of the party. The apartment in the Schuberts' house, though large, was unfortunately not well designed to hold large gatherings, consisting as it did of a series of small, cell-like rooms. Most of the rooms were lined with shelves crowded with curios, and tables holding prized vases and other memorabilia collected by the two very busy aunts.

Would the guests move from room to room in a congenial flow? Would the gathering of diverse people find subjects of mutual interest, or would there be long awkward silences? Would a respectable number of invitations be accepted?

Elizaveta Fedorovna was especially pleased when Andrey Ivanovich Kosich, a distant cousin on Elizaveta's side of the family, was the first to return his acceptance. Andrey Ivanovich was about the same age as Anyuta. His military career was advancing at a steady pace, and already he held an honorable position as an aide on the General Staff. If anyone had asked, Elizaveta would have described the young man as very well favored, very handsome, and possessed of impeccably good manners and charm.

In the last year, young Kosich had visited Palibino several times. He came to ask Vasily Vasilievich's advice on career matters. On these occasions Andrey Ivanovich had stayed longer than absolutely necessary, spending much of the time with his attractive cousin. And last fall, Anyuta had been allowed to make a special trip to Petersburg, to accompany the young officer to a military ball. At that time, Mother and Father had made it subtly known to Anyuta that they were very pleased the young man was showing a definite, though of course respectful, interest.

To Elizaveta's delight, in the next few days, almost all of the invited guests returned acceptance cards. The apartment would be filled to capacity.

On the evening of the party, the energies of the five women were concentrated on their appearance. Each wore a new dress. Each fussed with makeup and hair styling.

Looking into the glass, Sofya admired her new dress of dark green silk sewn especially for this occasion by the Aunties' favorite Petersburg dressmaker. This was Sofya's first evening gown, and like Anyuta, Sofya had insisted on not wearing a bustle. The loose folds of the skirt made a swishing noise as she walked. The short sleeves and low-cut bodice of the dress were trimmed with coy ruffles. With Anyuta's help, Sofya rouged her lips and penciled her eye brows. Her self-willed chestnut curls had been coaxed into an orderly pattern. The face that smiled back at her from the mirror was a little unfamiliar. Sofya thought it a pretty face, though certainly not beautiful like Anyuta's.

Mother entered the girls' room to conduct a final inspection. She fluffed the bodice ruffle of Sofya's dress and gave Anyuta's hair one last touch with the comb. Then Mother noticed an errant string of green thread hanging loosely from Sofya's left sleeve. In a voice made too loud by nervousness, Mother demanded a pair of scissors. After a moment of frantic search, the tool was found. Mother cut the offending string. "I hope that's the last. Turn around once more, Sofya, let me look carefully. Yes. That's the last."

Aunt Sofya entered. Noticing Sofya's uneasiness, she gave the girl a hug and lavished compliments on her grown-up appearance. Aunt Sofya also presented gifts: For Anyuta, a pair of diamond ear rings, for Sofya an emerald necklace with a single stone surrounded by silver filigree. The girls, dazzled, thanked their Aunt. "Put them on. Put them on," the older woman insisted.

The appointed time had come. Five magnificently dressed women received the arriving guests. Numerous candles were burning in all the rooms, giving unwanted heat as well as a welcome flickering light. Two waiters, in white shirts and formal coats, walked about, offering fruit, sweets, and perogie, finger-sized meat and fruit pies. Tea, wine and iced vodka were available at a sideboard.

Sofya sat in one of the rooms near the entrance hall, nervously fingering the stone of her necklace. Beside her was Nicholas Ivanovich Kosich, the younger brother of Andrey Ivanovich. The young man looked quite dashing in his uniform. Nicholas Ivanovich told her he was an artillery man. "In the regiment your Father once commanded," he added with pride. Sofya listened as he spoke boastfully of the advanced mathematics he had mastered to calculate trajectories. Sofya did her best to appear impressed. Had this distant cousin of hers stopped talking long enough, she would have told him that she had read about the techniques he was describing, and thought them rather simple. But he offered no such opportunity.

Just then Sofya saw Dostoevsky enter the next room. In an evident attempt to fit into the society he expected at the party, Fedor Mikhailovich had put on a black evening coat, but the garment was ill-fitting, and not at all flattering to his spare figure. His thinning red hair refused to submit to order and stood in disarray. Sofya's heart ached for him.

Dostoevsky's eyes were intently searching strangers' faces. He looked very nervous.

Smiling warmly, Mother approached him. While paying minimum attention to Nicholas Ivanovich, Sofya's mind and eye followed Dostoevsky. Mother was introducing him to some of the other guests. In discomfort and an apparently agitated state, he was only grunting monosyllables at them. To Sofya his response sounded more like a growl than a greeting. Sofya wanted to go to him, to put him at ease. But now Nicholas Ivanovich was asking her questions and she had to allow herself to be distracted.

Soon Sofya's companion was again absorbed in his own narration and Sofya could let her eyes search the nearby rooms for her Dostoevsky. Mother was introducing him to Andrey Ivanovich who had been speaking with Anyuta. Dostoevsky's eyes were focused on Anyuta and Andrey Ivanovich. It would have been impossible for him not to notice what a strikingly good-looking couple Anyuta and Andrey formed. Or that he himself was being introduced to his antithesis. Andrey was a handsome, composed young officer dashingly dressed in his guard's uniform with tight white pants showing his long, muscular limbs and a perfectly tailored green military jacket with silver epaulets accentuating his strong shoulders..

Without apparent explanation, Dostoevsky took Anyuta by the hand and led her to an unoccupied divan where he appeared to start an earnest and private discussion. For a moment Mother, Andrey Ivanovich, and, from the next room, Sofya, watched with surprise.

Sofya thought that she saw the young officer flush slightly, but in a moment his good manners prevailed and he turned his attention to Mother.

Sofya had to know what was happening. She interrupted her companion's monologue in the sweetest tone she could manage. "Could we adjourn to the other room? I'd like some refreshment."

The young man immediately rose. Suddenly unsure of himself, he profusely apologized for not anticipating her need. She smiled sweetly, and let her glance drop. She would imitate the silly mannerisms she had seen her sister use, if they would get her where she wanted to go. The young man responded, and they were soon in the other room.

Sofya's hands surrounded a cool glass of punch. Her companion had again begun a monologue, for which Sofya was grateful, because she needed only to nod her head occasionally. Her eyes, her ears, and her mind were free to absorb the scene unfolding.

Mother was now chatting with a retired officer, one of Father's friends. The man kept staring at Mother through his monocle and commenting in a fatherly--and yet not so fatherly--way: "Oh, such beauty! And your daughters, how beautiful they are. But my dear, you are more beautiful even than your daughters. Yes, even than your daughters!"

Mother flushed with pride, she let her glance drop. Sofya sighed, Mother was certainly a master of party mannerisms. As the man reached for Mother's hand, Mother stepped back just a little. Sofya heard Elizaveta Fedorovna gently excuse herself, pleading a need to speak with her daughter Anya.

Walking to the divan, Mother scolded gently. "Anya, dear, you're forgetting your other guests. I'm sure Fedor Mikhailovich does not want to occupy you in a tête-à-tête for the entire evening."

Anyuta started to rise.

"Anochka, please, another minute," said Fedor Mikhailovich, grasping her hand again. He leaned his body against Anyuta's to whisper into her ear.

Mother, watching, was turning pale. Sofya could hardly believe her ears. Here, in front of all these people, Dostoevsky had addressed her sister, a grown woman, with a name of endearment that indicated a strong degree of intimacy.

"Fedor Mikhailovich, please, do not forget yourself!" Anyuta scolded.

Dostoevsky flushed with embarrassment. Clearly the words had just slipped from his mouth. He rose to his feet. In a disturbing loud voice he stuttered, "Anya Vasilievna, please, another minute!"

At that moment, Sofya's companion stopped his monologue and looked in the direction of the loud voice. With a few half-thought-out questions, Sofya reengaged her companion's monologue, while she continued her observation.

Andrey Ivanovitch evidently also was observing the situation. He strode up to the trio, his face expressing determination, his body conveying the image of a charging knight. Mother, Anya and Dostoevsky were looking one to the other in a potentially explosive silence when Andrey Ivanovich joined them, positioning his body between Anyuta and Dostoevsky.

Forcefully, strengthened by the factor of surprise, he engaged Dostoevsky.

"Fedor Mikhailovich," Andrey Ivanovich began, fixing his eyes on Dostoevsky, "I have become embroiled in a discussion that demands the insight of someone of age and experience. Won't you join our group?" Andrey motioned vaguely to an adjoining room.

"What could warrant such a rude interruption?" Dostoevsky demanded.

"A matter of literature." Andrey Ivanovich reached for Dostoevsky's arm, evidently to lead him away. Dostoevsky recoiled.

"Talk to him, Fedor Mikhailovich," Anyuta urged, as she moved to Dostoevsky's side. Her voice conveyed sarcasm as she added, "I'd like to hear what questions of literature an officer might have."

Dostoevsky silently examined the young officer, then turned to Mother, whose cold expression offered no support. She moved closer to Andrey, and placed her hand lightly on the young man's arm, unmistakably announcing her preference and allegiance. Dostoevsky's face grew red. Mother didn't flinch. Her eyes reflected the ferocity of a she-bear defending her cub.

"I overheard some of your discussion. I've read the volume in question." Dostoevsky barely moved his lips as he replied to Andrey. "I understand it has been quite popular in Petersburg's German society. What of value can anyone expect from a German? All Germans are pig-headed, thinking only their way is right. They are corrupting the purity of Russia." Dostoevsky pronounced the word 'German' with a distinctly condescending, condemning manner.

Kosich's temper flared. "Sir, I am of German ancestry. I understand your remarks as an insult to myself and my family. If that was your intent, sir, I would be obliged to defend my honor."

Mother gasped. Her hand dropped from Kosich's arm. "Kosich, you're being much too rash!" Her look of firm, self-satisfied resolve had melted to fear at the suggestion of a duel.

Anyuta took Dostoevsky by the arm. "I'm sure Fedor Mikhailovich meant no insult to our cousin or to our family."

Dostoevsky's face had become very red. Sofya could see beads of perspiration forming on his forehead, but his eyes were still blazing. "Pardon, I meant no insult." Dostoevsky directed his apology to Anyuta, then to Mother, and only after an agonizing pause, to Kosich.

Sofya's escort had made a step towards Kosich, as if in support of his brother. Sofya caught his arm, holding him back from the encounter.

Nervously Anyuta responded, "Your apology is accepted by all of us, I'm sure. Now, let us discuss this book like the civilized, cultured individuals we all pride ourselves in being. Or let us talk about something else."

Dostoevsky and Kosich glared at each other once more. Mother stammered, desperately attempting to salvage the conversation. "There is something of value in the Lutheran ideals mentioned in the book you cited. Many theologians have argued strongly for the necessity of individual Bible reading."

"The great Lutheran theologian, Johann Ernst Schubert, argued just this point," Kosich, staring at Dostoevsky, spoke with pride. "He was Elizaveta Fedorovna's great-grandfather."

"I know of the Schuberts," Dostoevsky responded curtly. "You don't have to drag all your ancestors into this discussion." With an air of having put aside a tiresome, nagging child, Dostoevsky turned towards Mother. He could contain his rage no longer. "Madam! Do Russian society women care about the Bible or about Christ? They know Christ taught: 'Wives, be subject to your husbands--husbands, love your wives.' Russian mothers know this, and still engage in the most crass, materialistic match-making for their daughters." Dostoevsky's fiery look went to Andrey.

Before anyone had seized the chance to interrupt him, Dostoevsky continued, waving his arms in his anger: "Arranging marriages on the basis of property, money, position--never thinking of their daughters' or the suitors' welfare, inclinations, attractions."

Dostoevsky's left arm had struck a large vase on a nearby table. The urn tottered for a moment and then fell, to shatter with a loud noise upon the polished parquet floor.

For the space of two or three heartbeats the room was totally silent. Elizaveta Fedorovna stared at Fedor Mikhailovich. A tear had escaped and was running down her cheek, carrying with it a light blue trail of eye rouge.

"Excuse me, gentlemen." Elizaveta Fedorovna's voice quavered only slightly, "I will return in a moment." She started to walk from the room, then turned back. "Anya, I need your help."

Anya followed her.

A maid began fussing over the pieces of the destroyed urn.

Too late, Dostoevsky realized how harshly he had spoken. He began to apologize, too abjectly, to the stunned guests who gathered around for the accident.

Andrey Ivanovich turned without a word and walked away. His younger brother, who had been accompanying Sofya, went to Kosich, giving him the comfort of approving words. Guests who had been staring at the scene resumed their conversations a touch more loudly than before.

Dostoevsky sat on the divan, leaning forward, hiding his face from the world with his hands. Silently, Sofya sat next to him. She wanted to take his hand, to tell him his outburst was forgiven, that she understood his struggle to control his feelings. But she was too shy to touch him, or say anything. Soon the writer left the apartment, saying goodbye to no one.

That evening, as Sofya and Anyuta were preparing for sleep, Anyuta confessed that Dostoevsky had gravely disappointed her. The man was completely without social grace.

Sofya defended her friend. "Some people have a right and maybe even a duty to behave without inhibition, especially if they're upholding their beliefs. Dostoevsky was only stating what he believes is the truth."

"He could have done so with more grace," Anyuta insisted.

Anyuta tucked the down covers close around herself, then yawned and said good night. Sofya put out the lamp. She looked across at her sister. Anyuta just did not understand Dostoevsky.

Five days elapsed before Mother allowed Fedor Mikhailovich to reappear at the Schuberts'.

For a week Fedor Mikhailovich visited almost every day. Sometimes, Anyuta refused to postpone other activities in order to entertain him. At those times, Dostoevsky would talk with Sofya, who convinced herself that Dostoevsky enjoyed their meetings, more than the times he spent with the indifferent Anyuta .

One evening, Anyuta and Sofya were alone in the apartment. Anyuta sat at one end of the divan embroidering, as Sofya at the other end, reading aloud from a collection of Pushkin. Unexpectedly, Dostoevsky arrived.

"Where were you last night?" he blurted out angrily, confronting Anyuta.

"I was at a ball," she answered shortly, not looking up from her embroidery.

"I suppose Andrey Ivanovich was there?"

"Yes, as were many others."

"You danced with him? A waltz, I suppose. Or was it a Polish polka?"

Now Anyuta did put down her needlework. "Fedor Mikhailovich, there's no reason why I shouldn't enjoy myself in the few days I have left in Petersburg."

"You are a silly, frivolous little girl. Not a woman." Head lowered, he paced the length of the room. Looking up, his eyes caught Sofya's as she watched him, an open book in her lap. "I'm sure Sofya Vasilievna will not conduct herself so when she's grown. She'll be a beauty with brains!"

Sofya was confused. Dostoevsky thought her a beauty, but this violent outburst of jealousy must mean that he cared only for Anyuta. A silent, furious, angry jealousy towards Anyuta was taking over Sofya's mind, a violence of emotion that rivaled Dostoevsky's outburst.

Anyuta was glaring back at Dostoevsky. "Attending an occasional ball does not make me frivolous!"

Fedor Mikhailovich stopped.

Sofya looked at her sister. Anyuta was standing. She was almost as tall as Dostoevsky. Her hands were on her hips, and she leaned forward a little from the waist, putting her body in a defiant position directly in front of his. A fire of angry indignation blazed from Anyuta's eyes. Gradually Dostoevsky's face changed from raw jealousy to calculated indignation. He took a half step back and raised the shield of agitated ranting that he frequently hid behind.

His speech was slow at first, each syllable carefully pronounced. "Perhaps it's better that you are frivolous." When Anyuta didn't reply, he continued at an accelerating rate, "Better frivolous than one of the new women, the women of the Sixties as they call themselves. I've heard rumors about the deplorable actions of some young Sixties women here in Petersburg! Women of good family who have left their homes and are living in apartments with girls from the country. The new women think they can help the freed serfs become integrated into city life, or some such notion. These young women of the gentry even take jobs in factories to associate with the working women. These so-called 'new women' don't believe in God, marriage, or the fatherly love of the Tsar for his people. They despise all established institutions. You know what happens when belief in authority fails? Tragedy. Look at America. One deranged individual driven by a cause has just assassinated Lincoln! That's what happens when righteous individuals put themselves above the law." He paused for a moment, his mind obviously retreating to some distant refuge. More calmly he continued, "The women are called 'nihilists'. Turgenev invented the term to describe one of his ridiculous characters."

Anyuta interrupted. Her reply was loud and defiant. "I've read Turgenev's novel, Fathers and Children. The book distorts modern views. But what else should a reader expect from an old man writing about young ideas?"

Dostoevsky glared at her. Clearly he had taken offense.

Anyuta continued, "I think the women of whom you speak so scornfully are saints! They put their beliefs into action. They're not just talking about reforms, philosophizing about goodness. How can you be so blind as not to see this? How can you confine your love of humanity to paper?"

Dostoevsky grew pale. He swayed slightly. He sat down in the chair across from the divan.

Anyuta was still looking at him accusingly.

Dostoevsky put his hands to his head. The room was silent. Sofya rushed to Dostoevsky's side. Timidly she placed her hand on his. He pushed her hand away firmly, without looking at her.

He raised his head to stare at Anyuta. His eyes were blazing. He had been wounded. "You say such things to me? I've spent my time among the 'unhappy ones.' Thank God, not for any such naive ideas as these. I'll yield one point, perhaps it's not the women who are to blame. It's the fault of men. The university men who offer the women help and support, who tutor them to prepare them for entrance into foreign universities. The young men are using the women as part of their movement to Westernize Russia, to bringing about some kind of social revolution. They'll all end up as 'unhappy ones' in Siberia, mark my words!"

Anyuta turned and resumed her position on the divan. Forcing a calm attitude, she took up her embroidery before replying, "Has your Siberian experience made you afraid of action?"

Staring at the calm Anyuta, he appeared to struggle to control his anger. In a softer tone he continued, "These ridiculous notions of what some call social action will lead to nothing but unhappiness. And the notion that science will save man is utterly naive! Art, literature, music! These are the only means of human redemption!"

Sofya couldn't hold back. Her voice trembled, but she said firmly, "Science will save man, just as much as literature and art."

Dostoevsky turned toward her. Again, for a moment, she had the impression that he had utterly forgotten who she was. Suddenly she had to fight back tears.

"An educated young woman, like her sister, she is ready to defend her ideals." Dostoevsky's voice sounded condescending.

Sofya's hopes were crumbling.

Anyuta's response was as pointed as the embroidery needle she continued to wield so deftly. "You are a man of the world. You have known the charms of more than one educated woman. It's no use your sitting there and telling us otherwise."

"Anya!" Dostoevsky said sharply, "The girl is little more than a child. Watch what you say."

Sofya blushed with humiliation. He thought her a child! Now there was no holding back the tears.

Dostoevsky's agitation dissolved as he saw that she was hurt. "Sofya, forgive me. Your sister and I are the ones who are behaving like unruly children." He stood up. His large hand gently lifted her chin. He was looking only at her. "I believe all our moods would be improved by some music. Would you play Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique for us?"

He put his arm around her shoulder. He led her to the room with the piano. She didn't want to play, but she couldn't refuse him.

As she sat down he placed one of his hands on her shoulder. In a whisper, he added, "Play only the second movement."

It was hard to focus her tear-clouded eyes properly on the notes, but she began to play, forcing herself to concentrate. Soon the calming tones of the movement were touching her heart. The regular rhythms of her left hand, the tender passion of the notes, magically soothed her hurt. She played for him.

As Sofya coaxed the last chords of the second movement from the piano, she felt great satisfaction. Never before had she played so well and with so much feeling.

She hesitated--should she continue with the third movement? Would the heightened intensity of that section bring back uncomfortable feelings for herself and for the one who most concerned her, Fedor Mikhailovich? She waited for him to give her direction.

The room was totally silent behind her. Fedor Mikhailovich must have been awed, totally enraptured by her music.

She turned around. She was alone.

Faint voices were coming from the next room. Getting to her feet, Sofya moved quietly to the doorway. There were Anyuta and Fedor Mikhailovich on the divan, almost as on that other visit, when she had also played for him. The aging writer was red-faced and flustered, and as Sofya watched he raised Anyuta's hand to his lips and kissed it repeatedly. He was speaking quickly and with great earnestness, but so softly that Sofya could not hear the words. Seeing his attitude, the look on his face, there was no need to hear. Sofya realized that he was declaring his love for Anyuta. His passionate love!

And Anyuta was unresponsive! Her face was calm, her eyes turned coyly down. She allowed him to pour out his soul to her, as if all his love were no more than her due. At that moment, Sofya felt like Lazarus at the gate, begging for a drop of water, while in the next room, her sister was satiated at the banquet. Sofya again felt the violence of jealousy. She hated her sister! Hated her beauty, her charm, her composure.

She had allowed herself to believe in unattainable happiness. What a fool she had been! She tried to swallow, but couldn't. She sobbed, but no one heard.

She turned and ran for the welcome darkness of her bedroom, illuminated only by the flickering red light of the icon lamp in one corner. Falling on the bed, she abandoned herself to tears.

It might have been an hour later when Anyuta entered the room and lit the oil lamp. Her voice was calm. "Sofya, have you been weeping all this time? You just disappeared after playing that lovely piece. Fedor Mikhailovich wanted to congratulate you."

"Don't pretend you wanted me with you." Sofya blurted out, her words half-muffled by the pillow. "I heard you and Dostoevsky. I saw!"

For a while the room was silent except for Sofya's sobs.

"Sonechka," Anyuta hardly ever called her by the endearing form of her name. Sofya turned over. Her sister's face was not angry.

"Sonechka, this is ridiculous. You're fifteen, he's forty-four!. What kind of nonsense have you been imagining for yourself?" Anyuta's voice was just above a whisper.

"I love Fedor. Now you'll have him."

"So, you overheard his proposal." Anyuta touched Sofya's hand. "Dear little sister, don't be jealous. I'm very flattered by Fedor's request, but I haven't given him an answer."

"You haven't?"

"No. Sofya?" Anyuta's eyes were searching, there was no look of condescension, no more of the taunting attitude of the big sister. "Sofya, I must talk to someone. Tonight, especially, I must tell someone what I'm feeling. Be my friend."

Sofya stared at her sister for a long time. Hadn't Anyuta heard anything she, Sofya, had said? Was Anyuta so tied into her own feelings that she could ignore a cry of pain?

Sofya sighed as she realized that Anyuta could not see the pain in front of her. For all her beauty, talent, intelligence, and charm, Anyuta could not sense what was happening in another soul. Envy fell away, and Sofya felt a rush of love - love that was no longer childish, blind admiration - towards her sister. How strange, only a minute ago I thought I hated her. Now, I find she is very, very dear to me.

"Sonechka, I like Fedor very, very much." Then using the very words that had been in Sofya's mind, Anyuta said, "It's as if he sees my soul."

Anyuta continued, "There are many things in Fedor's life I'm not sure I'm ready to cope with. Our views on politics and religion are totally different. And Fedor demands and deserves utter devotion. I can't give that."

Sofya asked softly, "Do you love him?"

Anyuta hesitated. Then softly she answered, "No. I don't love him." She paused again, "But that's not why I'm not going to marry him. I know what I want from marriage. Companionship in freedom."

Anyuta's tone became lighter, "Someday I'll find someone who shares my thought, my goals, my beliefs. Then maybe I'll marry." After a moment she added, laughing, "Maybe neither of us will ever marry. We'll live together like Aunt Sofya and Aunt Alexandria. We might live the rest of our lives in this very house."

Anyuta leaned over to her sister. For a long while they held each other. Then, silently, the girls undressed and put out the lamp.

------------

-------------